In the NDC v AG & EC judgement (June 2020), the honourable Supreme Court said two things in respect of the birth certificate (BC). To better understand what the Court said, we need to first adopt and explain (strictly for the purposes of this discussion) two key terms – “bearer” and “holder”.

Bearer and Holder

Let’s call the person who, for the time being, holds and presents the BC as hers the “holder”. On the other hand, let’s call the person in whose name the BC is actually issued, the “bearer”.

From this bifurcation, it may be quite obvious that the holder of the BC will also be the bearer. Indeed, it is true that the holder is, in almost all cases, also the bearer. It is, however, also true that the holder of a BC is not always the bearer (e.g. in cases where Kofi fraudulently presents Kojo’s BC as Kofi’s).

The Birth Cert and Identification

Now, back to what the Court said: The first thing the Court said was that the BC is not a proof of identity. So, the Court noted:

“A birth certificate is not a form of identification. It does not establish the identity of the bearer. Nor does it link the holder with the information on the certificate.”

This is a valid point. It reveals the real situation where the holder of a BC may not be its bearer. The point must be accepted as valid because identification is an important element in the electoral process. For example, without an intervening identification mechanism, Kofi (the holder) can successfully present Kojo’s (the bearer) BC as Kofi’s.

Birth Cert and Citizenship

But the Court also said another thing. It said that the BC is not a proof of citizenship. The Court stated as follows:

“Quite obviously, it [a BC] provides no evidence of citizenship. It therefore does not satisfy the requirements of the article 42 of the Constitution.”

Further, the Court insisted:

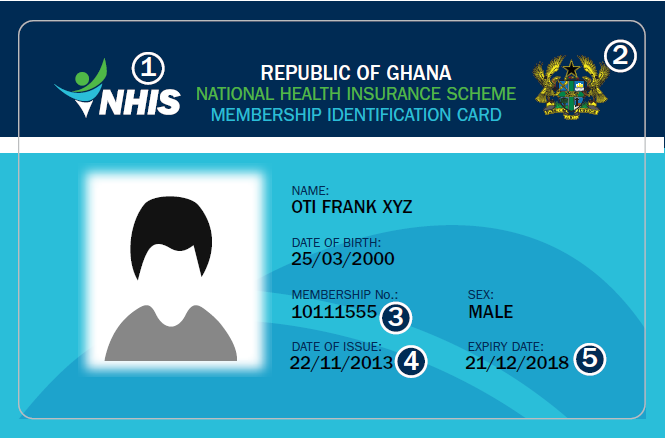

“In fact, as a form of identification, it is worse than the NHI card which was held to be unconstitutional as evidence of identification of a person who applies for registration as a voter in Abu Ramadan (No1), supra and Abu Ramadan (No.2), supra.”

First of all, the NHI card was not dislodged in Ramadan on grounds of identification – the card had an identification mechanism. Rather, it was dislodged on grounds of citizenship. Therefore, it was quite a significant mix-up that their Lordships compared the two instruments in this context.

Secondly, from the judgement, one may understand my Lords to be saying that because of its inability to prove the holder’s identity, the BC cannot also be accepted as evidence of citizenship. Let me say this in another way:

His Lordships seem to be saying that (a) citizenship is necessary for voter registration; (b) identification too is necessary for voter registration; (c) the BC cannot prove its holder’s identity; therefore (d) the BC is not evidence of citizenship.

One may notice that while the link between points (a), (b) and (c) are immaculate, the link between points (c) and (d) formed a kind of Bermuda link – quite dangerous. It conflates the issue if identification with the issue of proof of citizenship. However, since this is an entanglement problem, we may disentangle the points with the following corrective explanation:

(a) citizenship is necessary for voter registration; (b) identification too is necessary for voter registration; (c) the BC cannot prove it’s holder’s identity; therefore (d) the BC, by and of itself alone, cannot be accepted as a proof of identity and, thereby, (e) not also fit for the purposes of voter registration.

What is extremely difficult to accept, however, is the proposition which says that because of its inability to prove the holder’s identity, the BC is not and cannot also be accepted as evidence to prove citizenship.

Quite to the contrary, a more accurate proposition, I think, will be the one which says that the BC is a valid and complete means of proof of its bearer’s citizenship. Let me explain how the BC achieves this:

A person’s citizenship is determined along two main particulars: (a) her place of birth – jus soli; or (b) her parentage – jus sanguinis. Both of these particulars are contained in the BC. That, I think, makes the BC, having been duly issued, a valid evidence for establishing whether or not its bearer is a citizen.

Misrepresented Birth Certs

However, there’s another interesting line of argument. This argument seeks to propel the claim that the BC is basically rubbish because it could be forged, faked or misrepresented. That argument, too, can be quite difficult to sustain.

Let’s use currency (money) system to examine this argument: Currency is evidence of the value which is written on it. Because of this quality, currency is treated as legal tender – everyone is bound to accept it as a payment of debt to the value which is stated on it.

But, then, we have fake currency. Currency is fake if it lies about itself. A currency note lies about itself if any of theses two things happens: (a) if it is not duly issued, e.g. a forged note; or (b) if, though duly issued, its true value is not what it is offered for, e.g. passing off a GHC 1 note for a GHC 50 note.

The existence of fake currency notwithstanding, only a few people would seriously argue that currencies generally are not evidence of the value which is written on them. People would rather argue for a stiff punishment for currency fraud.

Let’s apply the currency framework to BCs – they (like passport, diplomas, etc) are both legal instruments. The BC is evidence of what is written on it. As indicated earlier, what is written on a BC are exactly what you need in order to know the bearer’s citizenship.

But we have fake BCs, too. A BC lies about itself if what it says is not what it is offered to prove. And, a BC is incapable of proving what it is offered to prove if any of these two things happens: (a) if it is not duly issued, e.g. a forged BC; or (b) if, though duly issued, its holder is not its bearer.

Like in the case of a currency note and, indeed, in the case of all other legal instruments, only a handful of people will seriously argue that BCs generally don’t prove their content simply because people do fake, forge or misrepresent a few BCs.

Indeed, the approach in such matters is not to rubbish or deny the instrument’s utility altogether but, rather, to enhance its integrity and sanctity. And, the best way to enhance or protect the instrument’s integrity is to ensure a rigorous regime for its issuance and a stiff punishment for it abuse.

Margin of Error

Finally, for the fake-BC line of argument to be taken seriously, it is not enough to simply say or prove that people do fake, forge or misrepresent the BC. After all, people do fake currency notes, degrees, passports, etc, but we still accept them as valid representation of the particulars they contain.

To reject the BC as evidence for proving citizenship, therefore, one must go beyond and show also that the number of fake, forged or misrepresented BCs are so overwhelming that it has rendered the entire BC system completely broken. This is a margin of error question which must be shown by cogent evidence.

Conclusion

Perhaps, if these humble lines had attracted the attention of their learned Lordships, the holding on the BC’s capacity to prove citizenship would have been a little different. In all, I think, the Court ought to begin to shift towards upholding the utility and integrity of State institutions and the legal documents they issue rather than lend its mighty support to forces that render such institutions weak and less useful.

Now, the big question – would the Court have added the BC to the list of identification documents in CI 126 even if it held that the BC provided evidence of citizenship? For so many reasons, I doubt.

For instance, in Ramadan (No.1), Wood CJ held that an identification document will not be fit for the electoral register’s purposes unless it cumulatively discloses the following:

(a) the holder’s identity (in terms of name, face or other biometric data);

(b) the holder’s citizenship (in terms of place of birth and parentage); AND

(c) the holder’s age (or date of birth).

As a matter of fact, the BC has not, in recent history, been used as a complete or autonomous identification document for voter registration purposes. And, that’s probably because the BC, by and of itself, though a complete proof of citizenship, lacks the identification quality that the electoral process needs.